Several years ago Valentin Dombrovsky translated Nadav Gur’s article about travel planning startups. I’ve read it several times since then and shared it in support of the exact same argument “you should never consider creating a travel planning startup”.

Yet there are some travel planning services in the market that have survived Startups Death Valley. And there are dozens of them, really!

If you want headache-free planning (“let the service suggest where to go and what to visit”) not knowing any appropriate service/app — you could stumble upon one of numerous “Best travel/itinerary planners” lists and even get stuck there realizing you first need time and effort to choose the right one.

My fellow has also recently expressed the exact same pain of headache-free planning. But with all these services on the market, I wouldn’t suggest anyone to him. That was the start of my search for the best trip planner.

Trip planners are “the joke of the industry”. It is (or was?) a popular option among travel startups to do, most of them failed to become sustainable businesses. And as they are mostly private companies not disclosing their financials we can only guess whether those that survived are already a profitable business or a seeing-their-way (i.e. burning-money) startup.

The markers we have are confusing.

Utrip CEO Gilad Berenstein was named GeekWire’s Young Entrepreneur of the Year in 2015. If you don’t dive deeper you wouldn’t find that at the same article it is written: “Berenstein says revenues are small, they are starting to grow”. Is having small revenues a prerequisite to be named the best entrepreneur? I thought the opposite is the case, and that we shouldn’t confuse entrepreneurs with startupers.

Interestingly enough, it was the same GeekWire that informed the world about the death of Utrip. The announced deadline of June 7 has already passed and to the moment Utrip is still live. They know Utrip is not profitable, stopped its development and even announced a closure date — but still, continue spending money on its support.

Is it a proper metaphor for the whole industry where even ones that survive (and declare profitability, as Inspirock does) are still not good enough?

In the research, I analyzed the services in 9 categories and highlighted good and excellent performance in the most important ones. Only 3 highlights are present:

- Broadness of possible request for Inspirock,

- Routing and transportation for Sygic Travel,

- UX for Classic Utrip.

| Max. | Inspirock | TripHobo | Sygic Travel |

Blink | Google Trips |

Roadtrippers | Tripplannera | Classic Utrip |

Timescenery | |

| Broadness of possible request | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Quality of suggestions | 5 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | - | 2 | 1 |

| Quantity of suggestions | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| Real use of preferences | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Routing and transportation | 5 | 2 | 2 | 4 | - | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Eating out | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Absence of other bugs (duplicates, etc.) | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | - | 3 | 2 |

| Variety of free functions | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| UX (predictability, smoothness, etc.) | 5 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | - | 4 | 1 |

| TOTAL | 57,6% | 45,5% | 48,5% | 35,0% | 48,5% | 36,4% | 27,8% | 51,5% | 45,5% |

The full research is available on Medium.

Note only one occasion for every service (and that most others have none).

There also are maximal achievements in Quantity of suggestions and Variety of free functions but I didn’t highlight them: having 3 of 3 or 2 of 2 is just OK here, while not having maximal figures is bad.

Why is it this way? I have several guesses:

- good quality is not cost-effective. To get a great product you have to improve your current product. It costs money that is not paid off by the improvement. And to stay at the market you have to cut off your costs.

- The reason for that: to improve the overall quality of suggestions the planner should improve the feed it gets from their partners and correct its mistakes.

Here is an example of the widespread mistake: I know no sources for travel planners’ that would support multi-level lists of attractions.

I mean there are parks, buildings, and fortresses that contain other attractions within:- Moscow Kremlin contains several cathedrals, Armory, etc.

- Central Park New in York contains numerous monuments, ponds, etc.

- Or an attraction is just a part of another one: e.g., Top of the Rock is situated in Rockefeller Center.

The list goes on and on. But they are parts of a single list everywhere.

And when users leave references and suggest a duration of a visit they don’t know there is another object in the base that they really should refer to. And thus they leave similar pictures and references to different objects.

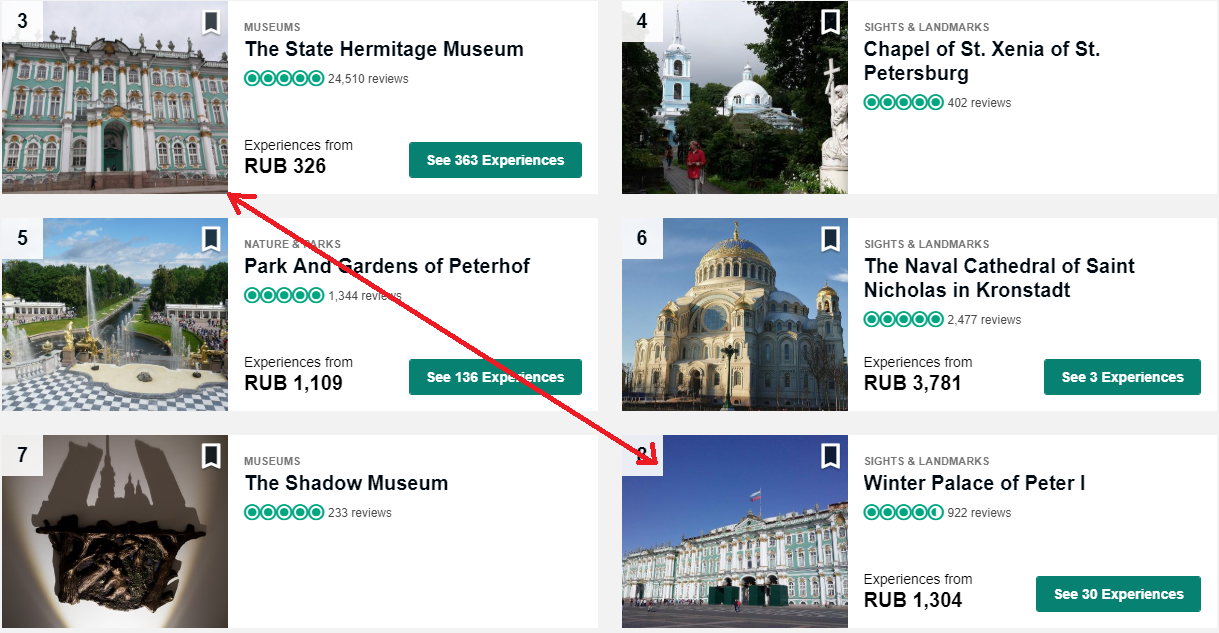

If you think I exxagerate the problem take TripAdvisor suggestions for Saint Petersburg. It features 2 different Winter Palaces (both occupied by The Hermitage Museum) as #3 and the #8 in the overall list of city’s attractions.

The reason for that? References and pictures left for #8 instead of #3.

The planner could deal with the situation in several ways:

- to feature only the attraction of upper level with its long suggested duration of visit leaving the user to decide on lower level himself,

- to feature only attractions of lower level meaning that the attraction of upper level will be visited anyway,

- to feature attractions of all levels.

But first, they should understand the hierarchy. Otherwise only the default third option is available.

How can planners get the hierarchy automatically?

The addresses of objects are different.

OK, pictures and references are similar. But they are different to a certain extent as well.

To correct these issues manually? This is the way Utrip (and not only them) took. I doubt its effectiveness, at least cost-effectiveness. You already know Utrip’s destiny.

And here what happens when a user sees 2 different suggestions with similar pictures and references.

She deals with the planner and by default concludes it is the mistake of the planner, not of its supplying partners (that she mostly doesn’t know).

And this is just one example. - The consequence: the need for an excellent planner is not real. Why?

Because users of travel planners are not eager to pay for the service themselves.

Yes, there are Roadtrippers and they are just an exclusion to the rule as they cover a slightly different market (where Expedia Group or Booking Holdings do not dominate).

Planners’ sources of information (TripAdvisor again but not only it) are free and already popular among potential clients of itinerary planners. To make users pay for the service it has to prove that it is not only more convenient (“all in one place” etc., you know it better than me) but actually better than what they use now.

Thus the service first should attract potential customers and then have them feel the difference. Both steps require huge spendings. It may seem an ordinary investment race (that Utrip has just failed in) unless you realize that it is trip planning — “the joke of the industry”. Are there any investors left who still want to put their money into this spoiled type of service? And even if you have the money — big players are not happy to give you traction. This is what Nadav Gur wrote in his article I started this research from.